Vagrant, Ansible and GitHub for Automated Development and Deployment

The big purpose of code, and technology in general, is minimizing effort. Depending on the definition, this is the same as maximizing convenience.

Software and technology have become sort of synonymous, but software is much younger. To coders and non-coders alike, it’s obvious that software is evolving like crazy. In public, the current phase of this evolution has us sharing, rating and paying for everything online, increasingly with our phones.

In “private”, the coders who build this maximally convenient world find ways to make their own work more convenient. They call it automation. What started with scripts to make programs from source code has exploded into a dizzying profusion of frameworks for automating all aspects of software development and deployment. If this sounds like hyperbole, or even pessimism, it’s probably because that’s what I felt when I first contemplated the automation ecosystem.

Recently I wanted to change the OS of the AWS box serving this site, from Amazon Linux to Ubuntu 14.04. I wanted the transition to be as painless as possible. More than anything, I wanted to be sure that once I had configured and tested locally, there would be no surprises deploying the site to production. I haven’t worked in DevOps, and my grasp of automation was weak, so I knew I’d have to read first, decide which tools were best for the job, and then learn to put them to use.

I’m here to report that my experience has given me cause for optimism. As young as it is, maybe coding has entered its postmodern phase, minus the bullshit. Code automation is self-regarding in a good way, and it makes our work more fun. It’s a good time to be a coder.

Works on My Machine

I first developed this site using MAMP. Then I registered my domain, configured an Elastic IP with AWS, set up a LAMP stack on the server and copied the code over using rsync. It didn’t seem unsophisticated at the time. There was frustration and debugging of the WOMM variety, but I figured it was part of the job, and that it might even build character.

This time, however, I wanted to avoid frustration. This is where Vagrant and Ansible come in. Combining them makes WOMM a thing of the past.

Ansible automates configuration. It translates a YAML playbook into shell commands and executes them on remote machines via SSH. One advantage of Ansible over other configuration managers is that you install and run it on your machine. There’s no agent on the remote server.

Vagrant makes it easy to spin up and tear down local VMs, and lets you provision them with tools like Ansible. It runs VMs in headless mode, meaning there is no UI, and access is via SSH to a local IP. This is great, because it’s exactly how you access production servers in the cloud. Vagrant provides convenience methods for choosing a hostname and mapping your project’s root directory on the VM to its local root directory, a la SSHFS. Using vagrant-hostsupdater, your host is automatically added and removed from your hosts file when you start and stop the VM.

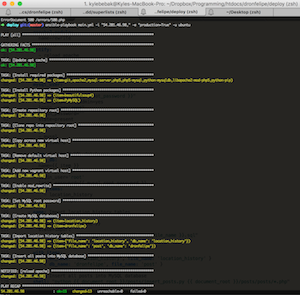

So, I built my deploy playbook locally, testing it against the Vagrant VM. I won’t go into details, beyond mentioning that I deploy site files by installing Git and cloning my site’s GitHub repo. Once dronfelipe.dev was working as expected, I spun up a new AWS box running Ubuntu 14.04 and configured it with the same playbook. The screenshot below shows the output of this moment of truth. I admit I had my fingers crossed, but there was no need. After all, the AWS machine was probably indistinguishable from the VM running on my computer. After 5 or 10 minutes the playbook finished. I went to the box’s public IP and there was my site!

To finish up, I disassociated my Elastic IP from the old Amazon Linux box and associated it with the new one, which took less than a minute.

Automated Testing: Git and Selenium

There are lots of tools and platforms to automate testing, but for my purposes Git is sufficient. The setup is rustic but effective. I have a pre-push hook in my repo which gets copied into .git/hooks on deployment. Every time I try to push code to GitHub, the hook runs functional tests and rejects commits that break the site. I use pre-push instead of pre-commit to make sure I’m not discouraged from committing early and often.

I write functional tests using Selenium. Selenium lets you code test scripts that fire up a browser and direct it from one page to another, clicking on things, entering text, and generally doing anything a user might do. You write tests that make assertions about what the HTML should look like, and how each page should react to various events, instead of having to do this by hand.

Once I push changes to GitHub, I have an Ansible playbook for pulling them down to the site, which I run from my machine. I know the changes won’t break anything because they’ve been vetted by the functional tests.

Big Picture

Automation is good. It lets you focus more on coding and less on “building character”. Much of it has come out of the need to coordinate big, diverse teams of developers, but there’s no reason you can’t use it to make working on your own projects more pleasant.

Git and GitHub (or analogous version control software and web apps) are prerequisites for automation, and essential to being a happy programmer. They take the fear and stress out of coding. They encourage you to keep everything related to your project in one place, let you share it with anyone, and guarantee that none of it gets lost. In the spirit of these ideas, my site and the code I use to automate it are on GitHub, in case you want to check it out.